Various Artists/Anthologies , Lonnie Brooks , Magic Slim , Pinetop Perkins , Johnny 'Big Moose' Walker

Living Chicago Blues II

Includes superstar Lonnie Brooks, two-fisted pianist Johnny "Big Moose" Walker, gritty, down-home Magic Slim and the Teardrops, and piano legend Pinetop Perkins. Grammy nominee.

Featuring:

The Lonnie Brooks Blues Band

Johnny 'Big Moose' Walker

Magic Slim and the Teardrops

Pinetop Perkins

Produced by Bruce Iglauer and Richard McLeese

Recorded at Mantra and Curtom Studios, Chicago, IL

Freddie Breitberg, Engineer, Assisted by Eddie B. Flick

Album Design by Ross & Harvey Graphics

Cover Photos by Jim Matusik

Photo Credits: Pete Lowry, Mindy Giles and D. Shigley

Thanks to Roy Filson, Rick Kreher, J.C. Moore and Dick Shurman

Coordinated for Compact Disc and Cassette re-release by Bob DePugh, David Forte and Bruce Iglauer

Liner Note Updates by Bruce Iglauer

Reissue Design and Production by Matt Minde

1991 Remastering by Tom Coyne at DMS, New York, NY

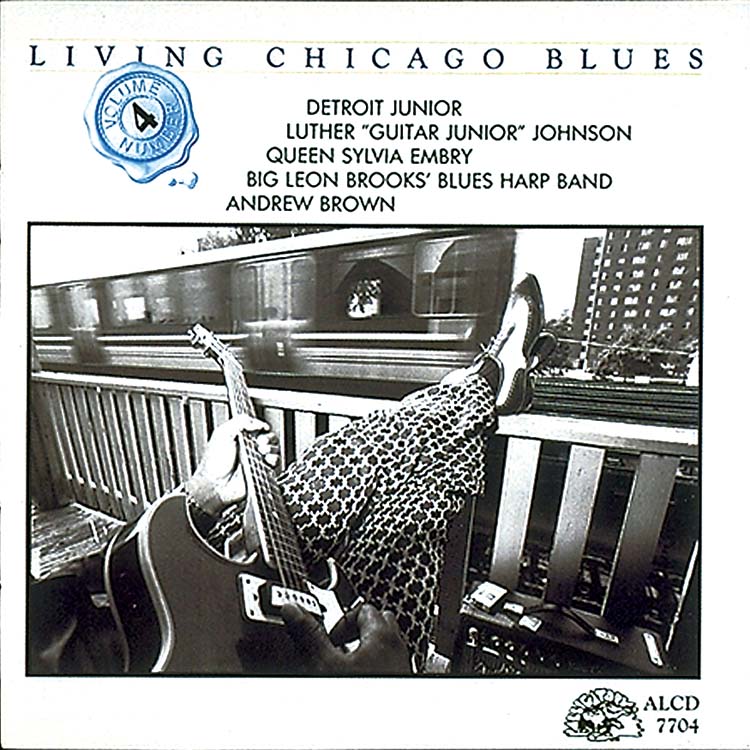

Also available:

ALCD 7703 LIVING CHICAGO BLUES, VOL. I

The Jimmy Johnson Blues Band

Eddie Shaw and the Wolf Gang

Left Hand Frank and His Blues Band

Carey Bell's Blues Harp Band

From the original 1978 release:

Every night in Chicago, the sounds of blues bands reverberate from narrow barrooms, basement taverns, and small, modest lounges throughout the city. At black neighborhood bars on the South and West Sides, decorated with Christmas tinsel, day-glo zodiac posters, handwritten signs on the walls; at the more publicized, fashionable nightspots on the North Side; or just at house parties out on the streets- the blues men and women of Chicago are singing, shouting, crying, laughing, celebrating. Songs of hard times, heartbreak, loneliness; songs to drive the blue feelings away, to rock the night and let the good times roll.

This is the living, continuing blues tradition of Chicago. Vibrant music with rich heritage of legendary names and classic songs from years gone by--but music not resigned to mere history. The blues still speaks to neighborhood crowds at clubs like Theresa’s, Florence’s, The Checkerboard, Pepper’s, Porter’s, Queen Bee’s and Morris Brown’s on the South Side, Eddie Shaw’s New 1815 Club, Ma Bea’s, The Majestic, The Golden Slipper, and The Poinciana on the West Side. And in recent years blues has drawn white audiences to popular North Side clubs: The Wise Fools Pub, Elsewhere, Kingston Mines, Biddy Milligan’s and others. The North Side clientele and décor differ, and the atmosphere is not so loose as in the black taverns. But, black or white, the blues clubs are much the same size and offer fine entertainment at similar prices. The small bands echo the sounds of the 1950s and ‘60s, but they’ve updated the music, too, with new patterns, new rhythms. In an era of pervasive rock, soul and disco trends, blues has thrived in the Chicago bars.

On weekends, clubgoers can find live blues at 20 or 30 clubs. Hundreds of singers and instrumentalists appear in the blues joints every year, just as they have ever since the 1940s and ‘50s, when thousands of blacks were arriving in Chicago from Mississippi, Arkansas, Tennessee, Alabama, and Louisiana. Today, black Southern musicians no longer migrate to the city in such numbers, but a whole new generation of bluesmen has grown up in the urban streets. And on the North Side, young white performers from the suburbs, the East and Midwest have moved in to participate with the blues veterans, sharing bands as well as bandstands.

The blues men of the ‘70s, like their predecessors, are men who live the blues, and live for the blues. Many have to work in factories, steel mills, or garages to make ends meet when the local blues gigs pay a man only $15 or $20 a night. But the blues is more than a weekend hobby to these musicians. The wages may be low, but the quality of the music is undeniably high. Chicago tavern musicians have set standards which have influenced popular music the world over. They may be featured as singers and bandleaders one night, while on the next gig they might work as sidemen in another band. Even on their nights off they’re likely to show up at a blues club, where patrons are continually treated to spontaneous jams and unadvertised guest performances. The crowds in the black clubs are mostly working people from the neighborhood. Sometimes they’re still dressed in work clothes. But the cab driver at the next table might also be a blues singer just back from a tour from France; maybe the mechanic sitting at the bar will suddenly be up on stage, blowing a harmonica or rocking the house with a guitar boogie.

Actually, “on stage” is a misnomer when it comes to most blues clubs. Bands often simply stand in a corner, or sit on their amplifiers, just a few feet from the audience. If there is a bandstand, it’s probably tiny and cramped, with barely enough room for four or five musicians at a time. Dressing rooms and special lounging areas for the stars are almost unheard of. Bluesmen share drinks and conversation with friends and neighbors between –and during-sets. In the blues bars, it’s a 9 p.m.-to-2 (or 4) a.m. world of live musical excitement, good natured-banter, friendly crowds, musicians who always have time for their fans, and honest songs wrought with power and emotion. And usually, all it costs to hear some of the world’s great music is a dollar at the door, if admission is charged at all, and 75 cents or a dollar a beer.

Yet most bluesmen have played their blues in taverns, week after week, year after year, unknown to all but the local patrons. There was a period of commercial blues recording in the 1950s, when companies like Chess and VeeJay were turning out hit singles, and the R&B disc jockeys and promoters were pushing the blues artists. But even then, the great majority of Chicago’s bluesmen were never able to record with any regularity, if indeed they recorded at all.

Today the powerful recording conglomerates show little interest in blues, and most blues singers must depend on small, independent companies which operate from storefronts or producers’ homes. The occasional 45s are distributed to ghetto record shops, jukeboxes, and amateur DJs who shout and spin records in the corner taverns. With luck, or enough money, a record might get a little airplay on the radio. The few Chicago companies which issue blues albums deal mainly with a market of white fans, students and collectors. Success in this market can mean gigs in college towns, or European tours which are more grueling than glamorous. Labels such as Delmark, Arhoolie, Prestige/Bluesville, Testament, and Vanguard were instrumental in putting many major Chicago bluesmen on LP for the first time during the 60s. Alligator’s Living Chicago Blues series, in fact, owes its inspirations to a historic sent of Vanguard albums (Chicago/The Blues/Today!), produced by Sam Charters in 1965/66. The men Charters recorded--Otis Rush, Junior Wells, James Cotton, Homesick James, the late Otis Spann, and others--went on to win international recognition and record several albums apiece for other labels. But today, many other excellent artists remain unrecorded, or with a mere handful of obscure releases to their credit. From this deep pool of overlooked or undiscovered talent come the artists who appear on the Living Chicago Blues series.

When Charters produced and annotated Chicago/The Blues/Today! he wrote, “In Chicago, on the South Side, it’s still today for the blues.” More than a decade later, it is still today for the blues in Chicago. As it was yesterday, as it will be tomorrow. Living Chicago Blues.

![The Alligator Christmas Collection [CD] The Alligator Christmas Collection [CD]](https://s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/alligator.prod.public/images/albums/9201.jpg)